Why I Often Avoid the Work I Care About Most

Understanding the inner force that prevents me from creating.

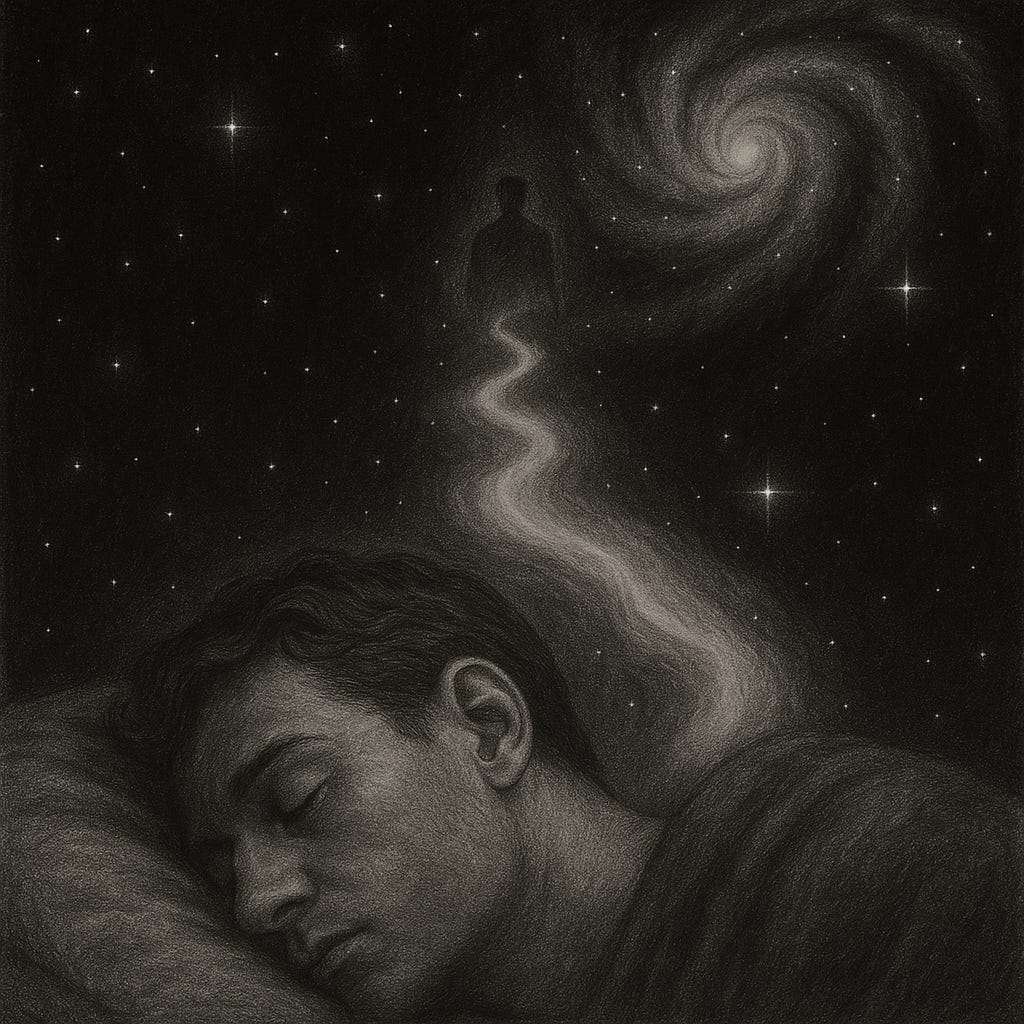

There’s a complex minefield, a psychological lattice, that seems uniquely designed to keep me from accomplishing the goals I’ve set for myself.

When I slipped out of bed this morning, I was struck by a surge of dread. This is a frequent occurrence. I knew what my goals were. I knew what I had to do to complete those goals. But I was also extremely tired. On mornings like this, everything, and I mean everything, seems to take an immense amount of effort.

Sometimes you climb out of bed in the morning and you think, I’m not going to make it, but you laugh inside—remembering all the times you’ve felt that way.

-Charles Bukowski

Eventually, I was able to recalibrate, adjusting to the expectations of the day. But that’s not the point. The point is that, before I was even fully awake, my mind was already tuned to the “You’re Gonna Fail” station. If I didn’t know any better, I would assume that my mind, or, part of it, really did want me to fail.

I understand, though, that my mind doesn’t want me to fail. There’s no malevolent force in my head, pulling the levers and pushing the buttons, bent on self-destruction. Rather, it’s a very deep-seated fear of both failure and success. And the best way to ensure that I neither fail nor succeed would be to opt out of participating at all.

That may sound odd, but it’s true.

In The War of Art, Steven Pressfield touches on fear being a manifestation of Resistance, which is a “force of nature” that keeps you from pursuing your life’s purpose.

He writes:

Resistance is experienced as fear; the degree of fear equates to the strength of Resistance. Therefore the more fear we feel about a specific enterprise, the more certain we can be that that enterprise is important to us and to the growth of our soul. That’s why we feel so much Resistance. If it meant nothing to us, there’d be no Resistance.

For this reason, I’ve been working hard to eliminate distractions that have previously kept me from my work. By narrowing the variables in my day, I stand a much better shot of sitting down to do what matters most—writing. This is a pivotal action step, because, when and if the Resistance approaches—lobbying for my focus to be devoted elsewhere—it will be easier to wave it away, given that I have dwindled my commitments down to the bare essentials.

In addition to limiting my daily variables, I must accept the terms of the challenge. Accept that writing is going to be, well, a challenge. Accept that the Resistance will be there to greet me every morning, insisting that it would be safer and easier if I didn’t go through with the goals I set for myself. Accept that, if I’m to succeed, I must endure and persevere, expecting nothing in the way of external validation.

For the Cynic philosophers—most notably Crates and Diogenes—a key virtue was Karteria (καρτερία), which is a Greek term that means “steadfast endurance in the face of difficulty.” Not only did the Cynics endure difficulty, they actively sought it out. They possessed a thick skin and resilient mind. This, for them, was the watermark of virtue.

Don’t be allergic to difficulty. Seek it out. Demand it.

Crates, in writing to Hermaiscus, noted that “[w]hether you like it or not, acquire the habit of working hard, then you won’t have to work hard. Idleness does not make work easy, it ensures that work will be hard.”1

My biggest priority right now is to make a habit of going on the offensive by attacking my pursuits.

Perhaps I fail. Perhaps I succeed. But I would have at least started.

The Cynic Philosophers: From Diogenes to Julian, trans. Robert Dobbin (London: Penguin Classics, 2012), 68.